First published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1909, ‘Secret Chambers’ is often compared to Daphne Du Maurier’s later book Rebecca. I was curious about the story but found it hard to track down in a readable copy online. I found it, transcribed it, and here you go! I would love to hear people’s thoughts on the story! I’ve included the original images from Harper’s here.

Naturally, they were discussing the Commission as they sat drinking their coffee in the drawing room after dinner – Arnold Hartzfield, the artist who had received it, his mother, and Sylvia, his wife; and although it had been the one topic mentioned among them for the last few days, it still remained the immediate and exclusive interest in the lives of these three people. Why not? It was a matter of vast importance in Arnold’s career. One of the larger American towns had recently builded a magnificent public library, and Hartzfield had been asked to paint ten pictures to fill the ten large panels.

“Isn’t it odd, mother,” Arnold’s hazel eyes were brilliant with twinkling reflections, and there was a sparkle, even a momentary content, on his keen, eager face, “and isn’t it fortunate that I should actually have a studio to my hand so near L____? A railway runs through the village now, and it’s only an hour’s ride to town. A beautifully restful old spot! I’m speaking of Altamont, Sylvia, the place mother owned and gave to me, and where I built an outdoor studio. Whew! The dreams I used to dream there! He passed his hand across his brow in brief reverie, his face again assuming its customary expression in repose, a sort of baffled, disappointed eagerness, repression, even a faint cynical bitterness; but these in turn faded in the glow of purpose, the new determination of achievement which the bestowal of the Commission had aroused in him.

“Of course,” he went on, “it is absolutely necessary that I should be near the library for a time and give a thorough study to the lighting and proportions. So,” in quite matter-of-fact tones, “we will go back there instead of my trying to do the work here.”

Sylvia looked up bewildered, and gazed about the harmonious room, admittedly one of the most artistic in Paris, with its pieces of silver and pewter shining against the subdued peacock hues of walls and hangings, blues and greens and bronzes suavely blended. What had he been saying? Impossibilities.

But although her first quick glance about had been one of dismay, she said nothing. That was like Sylvia. She was not in the least impulsive, and this quality of inner balance and harmony, the antithesis of his own mercurial temperament, was what had at first attracted Hartzfield to her.

His mother was the first to break the silence. Do you remember the picture of Love that you painted at Altamont, Arnold? I wish-” she paused suddenly, with a hasty, almost furtive glance at Sylvia.

Hartzfield threw back his head with a flash of storm in his eyes. “I beg you will never mention that subject to me again, he cried, with harsh irritability. He pushed back his chair gratingly and left the room; a few moments later the two women heard him open the piano and begin to play, crashing volcanic chords.

“Mother,” said Sylvia presently, her clear, gray eyes fixed steadily on those of the older woman, what did you mean and why was Arnold annoyed when that picture, of Love, was mentioned?”

“Nothing, really,” she said, hesitating, and frankly appearing to ponder. “I assure of that, Sylvia. A buried incident in his career. Since he has not spoken of it to you, and since you are a wise woman, I advise you to let it sink into oblivion, but-” she spoke with an earnestness and depth of feeling unusual with her. “Take my advice. Amuse yourself by having the whole house done over as soon as you get to Altamont.2

“But why?” asked Sylvia, in surprise. “Arnold said that it was charming.”

“He forgets,” said Mrs. Hartzfield shortly. “All men forget. He has never been near the place since Adele died, and at that time, in the first-” she hesitated – “sentimentality,” Sylvia noticed that she did not say grief – “he gave orders that nothing be changed; but I stayed there a month, two years ago, and let me tell you, my dear, that I have never had anything get so on my nerves. I am not impressionable nor superstitious but-” she shivered and lifted her eyebrows expressively.

“Why?” asked Sylvia.

Mrs. Hartzfield threw out her hands with an expansive gesture. “The whole place is full of her,” she said – “full of her. She was a feminine Narcissus, and every person she met must be a pool and reflect her. She would tolerate no backgrounds, nor vistas, nor any relieving scenery: she wanted to fill the whole picture from frame to frame, and she could not even have conceived the idea of being one of a group. When she entered a room, she filled it. She filled a house. She took complete possession of your imagination, your will, or she knew the reason why, and she crowded everything else out of Arnold. In the few years they were married, the promise of his youth, his high dreams, his consecration of purpose, all went down in ashes. You did not know him in those first years after her death. When you met him, his interest in his work was gradually reviving, his individuality was beginning to assert itself, to flutter vaguely its maimed wings; and you, Sylvia,” the bitterness of her tones lost in unwonted tenderness, “you have helped to heal and restore and obliterate.”

Sylvia laid her cheek against the older woman’s in one of her rare caresses; but she did not speak. Her eyes had a peculiar inward glow. She had never thought much about Adele before, but Mrs. Hartzfield’s words had aroused a curiosity, acute, sudden, almost stinging. Arnold rarely spoke of his first wife, and then almost casually, and Mrs. Hartzfield had never mentioned her to Sylvia before. And now, all at once, Sylvia felt that she longed, thirsted to know more of this love of Arnold’s youth.

“Were you not fond of her? Was she not attractive?” she asked.

“Oh, adorable, in a way,” returned Mrs. Hartzfield carelessly, “But the most pervasive – yes, altogether the most pervasive – personality I have ever encountered.”

“Was she very delicate? An invalid?”

“Adele?” in evident surprise. “Oh, not at all. Full of life.”

“Of what did she die?”

Mrs. Hartzfield was intently examining a photograph on the table. “Oh, her death was very sudden.” Her tone was infused with a cold, even curt, finality. “But why,” impatiently, “are we on such depressing themes?”

That was the last as well as the first time that the subject either of Adele or of the picture was ever mentioned between them. In the late summer Arnold and Sylvia sailed, and whatever apprehensions her homesick heart may have nursed on the voyage, Sylvia felt them all vanish on the day they arrived at Altamont. She always retained a delightful memory of the drive first through the village and then through a long stretch of woodland. She affirmed that it was a revelation of colour to her; a sky as blue and as brilliant as a sapphire, and against it bold columns of maple-flame, the yellow, fluttering gold of elms and beeches, and the gorgeous sombre bronze of oaks; a splendid trumpet-call of color lifting the heart as on waves of music.

The house stood on a little knoll, hardly a hill, but rising ground. Houses which have harbored many generations have a very distinct character of their own, and this mansion was no exception not the rule. The impression it created on the mind was of a sort of stately serenity. It was built in the Colonial style, with a row of Corinthian pillars across the front, and flight of stone steps leading up to a flagged porch. Of a soft cream-color, it was flanked on either side by some fine old oaks and beeches, not too near to impede the view of far-stretching woods and noble hills.

“By Jove!” said Hartzfield, his head out of the carriage window, “the old place isn’t so bad, after all, is it? That is my studio younger, Sylvia,” pointing out a small building at some distance from the house. “And here is good old Judy to meet us,” as a tall, dark, angular Irish-woman came across the porch and to the top of the steps to welcome them.

Judy herself showed the new mistress through the hall and up the wide, shallow stairs to a suite of three rooms.

“These are the guest chambers, Mrs. Hartzfield,” – her words allayed a latent and shrinking fear of Sylvia’s that through some stupidity she might have been given the apartments of Adele. “The bedroom, bath, and sitting-room. They are all done in blue, you see. I hope you like blue?”

As Judy asked this commonplace question, Sylvia was struck by something in her manner; she seemed to wait with anxiety the answer.

“Indeed, I am very fond of blue,” replied Sylvia. “It is my favorite color. I will slip into another gown and then come down. I am hungry. Will dinner be ready soon?”

“It shall be served whenever you wish, Mrs. Hartzfield.” Judy was already unpacking the trunks with the skill and touch of much experience.

Half an hour later, Sylvia was smiling at Arnold across the dinner table. “Judy is wonderful, an artist!” she exclaimed. “Look at the arrangement of those flowers! It is worthy of Japan. But, Arnold,” as a beautiful dish of grapes and peaches was offered her, “is this an American custom, having fruit served first at dinner?”

“An American custom!” he repeated. “Oh dear, no. It is a stupid custom of this house.” His mouth twisted wryly. “Abolish it. Abolish it by all means.”

“Why? It is rather odd and pleasing.” Then, a few moments later: “Arnold! What dreams of candle-shades! Ah,” examining them more closely, “they have been painted by no tyro. Have you looked at them?”

Arnold barely glanced at the pink candle-shades, painted with tiny crimson roses wreathing the miniatures of lovely women.

“Yes,” went on Sylvia, “done by a master. Sorchon? Would he condescend-”

There was a sardonic smile on Hartzfield’s face. His eyes were hard. Sylvia did not know before that hazel eyes could look like steel.

“No,” he said, grimly. “Emphatically Sorchon would not condescend. It was I-I.”

“You!” she cried, incredulously. “You who must always have a canvas as wide as a church door!”

He was looking at her with a peculiar intensity, and yet she felt as if he did not see her at all. His mouth was twisted in a smile of cynical mirth, the steel of his eyes flashed. “My hair was clipped to the roots, and my eyes were blinded, and I was put in the treadmill.” He passed his hand over the thick, short growth. “I resisted. Believe me, I resisted; but Delilah is sure to win.”

He twirled one of the candle-shades nearest him for a few minutes, his face still contracted in that distorted smile; and then slightly shrugging his shoulders after his mother’s fashion, devoted himself to his dinner.

He scarcely spoke again, and at the conclusion of the meal wandered into the hall, and opening the piano, began to play; and Sylvia, after listening a bit, got up from her chair and strolled restlessly about. Most of the rooms on the first floor opened into the hall, and they were all brilliantly lighted, apparently inviting inspection. Her first impression of the house, gained from its exterior, was but enhanced and confirmed by her view of the interior. It was remarkably light and spacious, one might say even gay in effect.

“I wonder if I am out of the picture completely,” smiled Sylvia to herself. “This seems the chosen nest, the loved retreat of an enchantingly pretty and coquettish woman. If my grave and sedate self is to be part of the composition, I should be in the sombre and flowing robes of a French abbess.”

She had moved slowly through the library and a charming sitting-room, and had now reached the drawing-room. It was by far the most brilliant apartment of the series, lacking entirely the rather severe formality characteristic of drawing-rooms in general. All in pink and silver, it gave out a sheen and shimmer that Sylvia found almost dazzling.

Overcrowded, overdecorated as it was, its ornaments, many of them, beautiful and unique, yet Sylvia’s eye was almost immediately caught and held by a picture on the opposite wall, the portrait of a beautiful woman. Her exquisitely rounded shoulders rose from billows of tulle which fell low over the arms; the head, literally sunning over with curls, was bent, and the yes glanced upward through long lashes with an arch and petulant coquetry.

“Pretty creature!” exclaimed Sylvia, then, with a shock, followed by a vivid increase of interest, she realized that this must be Adele.

She had been standing with one hand on the back of a straight little chair, and now she drew it toward her and sat down, the involuntary smile with which we greet an image of beauty fading from her face. What radiance! Here in this room, so decorated that tit gave out sparkles like a jewel, where there were any number of objects, each beautiful in itself, to attract the attention, the picture dominated and eclipsed them all. Sylvia felt as if she had never seen feminine loveliness before, nor realized its possibilities for expressing the joy of life. But as she continued to study the portrait she saw there was that in the face which all the glow and radiance of a most beauty but thinly masked. It had been in the flesh a mutable face, and as Slyvia continued to gaze steadily at it she seemed to see it change before her eyes. There was something in those pictured eyes that mocked and refuted the appealing sweetness of that rose-leaf smile. He who ran might read that it was an emotional face passionate to weakness; but few would discern beneath that soft, peach-bloom flesh the iron of a powerful will and of a tenacious and unscrupulous purpose.

Sylvia did not see all this clearly, but something of it she divined dimly and in part. “What a power!” she muttered rising – “what a power!” and then stopped suddenly; the portrait appeared to surround her, for the several large mirrors which the room contained seemed to give back a thousand reflections of it. her own image, too, was presented from half a dozen angles. Slender, erect, her long, dull blue gown falling about her, her pale, upheld, cameo face, the dark, cloudy hair – yet she, the living, breathing woman, was as the shadow, while the portrait, a thing of paint, conveyed infinitely more effectively the illusion of life, the pride of the flesh.

She strolled out into the hall again. A wood fire was burning on the broad hearth, there were no other lights, and Arnold still sat at the piano; but the music his fingers evoked was evidently the mere accompaniment of his thoughts. His head was thrown back, his ees gazed unseeingly before him, narrowed, concentrated, introspective. He did not even see Sylvia as she stood for a moment beside him. He had entirely abandoned himself to the absorbed contemplation of the vision. The creative mood was upon him. These were the signs by which she had grown to recognize it. Noiselessly she moved away from him and sank softly into a chair by the fire. Even before their marriage she had become accustomed to these moods and knew when to efface herself. Their love, she rejoiced to think, had been an unhindered progression. Begun in genuine comradeship, it seemed to her that they were always graduating through various phases of friendship into an ever rarer and more understanding love and sympathy.

For perhaps an hour they sat there, she gazing into the flames, and he drifting from one bit of melody into another, until at last he closed with a crash of chords and jumped to his feet.

“Sylvia!” he cried, his eyes shining, his face palely irradiated, “I’ve got it, the whole conception! It has been more or less hazy, lacking coherence and definiteness. Oh, you can’t dream how disturbing that is! But now it is perfectly clear. I shall begin work tomorrow.”

“Oh, what is it?” she cried, all eager sympathy.

“No. I shall keep it for a surprise. Oh, truly,” at her obvious disappointment, “I am not saying that to tease you; but because I value your criticism above that of any one I know, and I am determined in this important instance to have the benefit of your first, fresh impression of the completed work.

“Very well,” she smiled, although a bit ruefully. “I see what you mean, and if I can help you best that way, well and good; but I cannot pretend that I am not disappointed, because I am dreadfully. I thought the Commission would be our principal interest and topic of conversation here; but I shall manage to put in my time very well without you, since I have to. It is a charming, restful spot, and I shall devote my time to my music and those other studies that I have been meaning to take up for a long time.”

For the next two or three weeks the weather continued fine, October at its mellowest and best, and Sylvia spent the greater part of each day out-of-doors. She never grew tired of wandering through the woods watching the leaves flutter down through the dreamy sunlight, and the hazes on the hills melt through all the shades of sun-dusted violet and amethyst. But in spite of her books and her music, the studies that she had contemplated with so much enthusiasm, she suffered a growing dread of her evenings – in fact, of any of the time that she must remain indoors; for, take herself to task as she would for such irrational vagaries, she felt more and more during the hours she spent within the house as if she were not the rather solitary mistress of Arnold’s home, but a guest thrown into a constant enforced intimacy with her hostess.

One day Judy suggested to Sylvia that she make a tour of the house. It seemed only fitting that as mistress of the mansion she should do so, and Sylvia assented. Over the whole place, from attic to cellar, they went, Sylvia bestowing encomiums on the perfect order in which everything was kept. But when Judy unlocked the door leading to Adele’s apartments, Sylvia was aware of a mental reluctance, a dread of entering, and yet a tingling curiosity which would not be assuaged save by a sight of these rooms which had always been kept just as Adele left them.

As Judy stood aside for her to enter, Sylvia thought of all the tales she had read in which the apartments of the departed are kept intact, and almost she expected to be met by a waft of musty air, laden with dead and sorrowful memories; but the sunlight streamed through the open windows, and the breath of the autumn morning was sweet and fresh. In the draught created by the opening and closing of doors there was the stir and movement of draperies, the sudden sweep inward of a long silken curtain, creating the momentary illusion of the advance of a rose-gowned, buoyant figure, an illusion enhanced by the wafting fragrance of roses and jasmine with which the very hangings on the walls were impregnated; and the shimmer and play of moted sunbeams over white rugs and polished floor was like dancing feet running to greet a guest.

The rooms were crowded, full of all the thousand and one absurd costly trinkets that Adele had loved, and portraits, photographs, taken at every angle and in every possible type of costume, filled every available space.

“Would you like to see her dresses?” asked Judy. “There are presses full of them.”

“Oh no, no, no!” cried Sylvia, sharply, “I couldn’t pry like that.”

Judy glanced at her with an odd, grim little smile. “She’d have rummaged through everything before now,” she said.

Slyvia had picked up a photograph in an ornate gold and silver frame. “How lovely she must have been!”

“There’s no photograph or even paintings that can give an idea of her,” Judy said. “The photographs can’t give her color and the paintings can’t give her life, not even an idea of it. That’s what she was all life and color. She could wheedle a stick or a stone, and she did it, too. She couldn’t let anything pass her without paying toll. She’d lay herself out to please; but she got more than she gave, Miss Sylvia, she got more than she gave.” Judy’s always grim tones had grown grimmer, almost reminiscently tragic, while her eyes bent on Sylvia held a strange Celtic insight. “You were telling me a few days ago that there wasn’t anything I couldn’t do. Well, I was trained in a hard school, the school of Miss Adele. She had no mercy on any one. She took a fancy to me, and I had to do everything – be housekeeper, lady’s maid, sempstress, everything. Why, I’m only thirty-five, Mrs. Hartzfield, and I look fifty. Miss Adele wore me out. You see, everything had to be just right, or she’d know why, and times when I thought I’d drop, it would be, ‘Brush my hair, Judy; I’m tired,’ or ringing me up in the dead of night to read to her because she couldn’t sleep. Oh, she was cruel hard, Miss Sylvia; and yet, since she’s gone, her and her tempers and her tears and her smiles and her coaxings, someway the color and laughter and excitement’s gone out of life. It’s like a dish without salt.”

“But how did a person like that endure the country here?” Sylvia could not forbear the question.

“She was in love with her husband,” Judy lifted her eyes. “Lord! How she loved him!”

“Was she long ill, Judy?” Sylvia’s voice was low.

“Ill! Her? Oh, you mean at the last. No, Mrs. Hartzfield.” The tone was curt with a repressed emotion Sylvia could not translate, and from maid to mistress authoritatively final. “It is getting late. It must be luncheon-time.” Judy fingered her keys and moved toward the door.

Daily, Sylvia found her interest focussed more steadily upon one subject – Adele. There was always something, some trifle either by way of incident or discovery, to incite her in following mentally the mazes of this fascinating personality; but not without protest. Ah, no. There was the continual struggle, the wearing mental argument, when all the sane and healthy and normal forces of her nature rebelled against this obsession.

As a last stand she suggested to Arnold one morning at the breakfast table that they have some people to stop with them. But he immediately negatived this idea, looking at her meanwhile with a surprised and almost unbelieving irritation.

“Sylvia! Of what are you thinking? You know that at this stage of my work I cannot have a lot of people to bother me. If you are lonely or bored here, and” – in quick afterthought-“no doubt you are, my dear, why do you not run off somewhere and amuse yourself?”

“You forget,” she said, coldly and gently, “that it is many years since I have lived in America, and that I have very few affiliations here.”

He threw out his hands with a quick gesture as if disclaiming all responsibility and resenting having it thrust upon him. “I’m sorry, my dear, but really you’ll have to arrange those things to suit yourself.” Then in contrition he jumped from his chair and running around the table, threw an arm about her shoulders. “You know, Sylvia, how outside things torture me when I’ve got the mood, and, by Jove! I’ve got it, or it’s got me.” There was a strong, almost wondering exultation in his voice.

“I know,” she smiled up at him, herself again. “Go right on with your work and never give me a thought. You know that I always do very well. And you understand that ‘the mood’ is not to be disturbed for a moment by any little vagaries of mine.”

“Dear Sylvia,” he touched her hair lightly with his lips, “you have made me understand that in the past, to my eternal gratitude.”

For two or three days thereafter she succeeded in banishing her disquieting fancies, but gradually they asserted themselves more positively than before, and her resistance to this influence which permeated the atmosphere in which she moved gave way. The delicacy which had withheld her from probing into the psychological relations of Arnold and Adele began to appear to her as a wire-drawn and imaginary scruple. In this new point of view Arnold already seemed a different person to her, and her analysis of him, her supposition of the traits of character and phases of emotion he would exhibit under different conditions occupied her mind. She strove to reason clearly and logically from the known to the unknown of him, without particular success, but the deepening suspicion of injustice, neglect, misunderstanding to the point of cruelty to this long-dead Adele was unchecked: and as she opened her thought to it the stream of conjecture widened and increased in volume. Adele had so far revealed herself as to show that she was broken-hearted. Had she died of a broken heart? Absurd! Impossible! That superabundant vitality had never so succumbed.

But what was the malady which had cut her off in the splendid tide of her health? Why had she, Sylvia, never heard? When she had asked Mrs. Hartzfield and again when she had asked Judy, they had both looked at her so strangely, with the same quick, furtive glance, and had answered with the same curt inflection. “Yes, she died very suddenly.” Surely it was odd!

Then through the unbroken silence of the room there seemed to peal the question, infinitely more startling and compelling than if audible, “How did Adele die?” The very walls echoed it. Sylvia suddenly sat upright, her hand on her wildly beating heart, while the question thundered its reiterations in her brain.

She started up. She would go now at once and ask Judy. No; she knew instinctively that Judy would evade her, perhaps lie to her. Judy was out of the question. She would demand of Arnold that he tell her. She was half-way across the porch going toward the studio, when she gave the matter consideration, her finger on her lip. Perhaps in this new Arnold, this stranger with whom she dwelt, she would also encounter evasions and subterfuges. Why turn to either Judy or himself, when she had a far surer method of discovery? She had so far resented the encroachments and invasions of Adele, but now the foundations of her resistance, long undermined, gave way, her bulwarks fell, her barriers crumbled. She was defenceless.

Her poise, her calm strength, had entirely deserted her. Through the very violence of her emotions, shades and subtleties of feeling of which she had hitherto been ignorant were revealed to her, and in the silence of this snowbound, ice-locked winter, in this strange, featureless, incalculable world of visions wherein she groped, she was conscious of a more thrilling and intense life than she had ever dreamed of. It seemed to her that she was a harp, ever being tuned higher and higher for some mighty theme.

One evening as Arnold sat dreaming over the piano, striking vague chords and drifting into broken harmonies, an almost irresistible impulse seized her to go to him, to cry to him: “Shake of this obsession of work, Arnold. Stop grasping after the ideal. Come back to earth, sweetheart, to love, and to me.”

She crushed back this inclination, but she could not repress her desire to woo him, to win him to remember her.

Slipping gently behind him, she threw her arms bout his neck and pressed her cheek against his. “Dearest, she murmured – “dearest.” He suffered her caress, even leaned his cheek against hers, but did not speak. His eyes were still fixed upon some point beyond the mortal vision, and he still weaved his broken, improvised harmonies.

She could not bear it. A wave of anguish engulfed her. “Arnold!” she cried, her voice broken, “it is weeks since you have kissed me. It is months since you have treated me with the old intimacy and tenderness. Do you no longer love me?

The lines so perceptible now in his sensitive face deepened; chords crashed and broke under his fingers. “Don’t!” he cried, sharply. “My work gives me all the emotion that I can bear. Ah-h-h!” He shivered and leaned more heavily against her. “The tortures of the last few days! How I have groped for the proper treatment, how it has haunted and eluded me! This is not like you, Sylvia.” He turned to her with a deep reproach in his eyes, and then seemed to see her for the first time. “Adele!” he gasped, hoarsely, almost inaudibly. “Ah, recovering himself, although the beads of sweat stood out on his pale forehead. “I thought for a moment – Why are you wearing rose-colour?”

“There is no reason why I should not,” she answered, coldly. “I had on this gown at dinner, but you did not notice it. She turned and left him, going into the drawing-room, and there again walked the floor, her hands pressed to her temples, her whole figure shaken by tearless gusts of passion. She looked up at the portrait of Adele, the exquisite shoulders rising from the billows of tulle, the eyes looking upward through the long lashes with the most alluring coquetry.

“What would you do?” Sylvia whispered. “What would you do? Oh, you poor thing, what did you do?”

The sound of Arnold’s music came softly to her ears. It was no longer broken, but continuous and flowing. He was lost in his visions again; visions over which he so dreamed and gloated that he could not even see her in her gown like crushed rose-leaves. She determined now that she, too, would see them and in tangible form; so, snatching up a cloak, she stole silently from the house.

It was a moonless night, but a pallid light was reflected from the snow which stretched far and white. The black trees were like a mighty guard of sentinel shadows, and Sylvia sped among them, flying over the snow in her light slippers, indifferent to cold or wet. Swept along as a leaf without volition of her own, a wild exultation shook her. Now, now she meant to search the springs of Arnold’s passion, all those secret chambers of his soul so securely locked from her.

A dim light shone from the studio. She tried the outer door. It was unlocked, and with a sigh of relief she passed through it. The inner door, too, yielded to her touch, and softly she pushed it open and crept in. The lofty sky-lighted room was warm and very quiet, with shaded lights dimly burning, and the atmosphere was soothingly calm and peaceful; but although it arrested her for a moment, it could not long assuage the storm of her spirit. Hastily she turned high the lights and glanced eagerly, hungrily, about her. The room was full of tall canvases leaning against easels. One or two of the panels were almost finished; the rest were in various stages of completion.

Above the central canvas were great golden letters:

“YE SHALL KNOW THE TRUTH AND THE TRUTH SHALL MAKE YOU FREE”

and on this panel Arnold had depicted Jesus of Nazareth as He toiled a prisoner up the slope of Calvary, bearing upon His back the cross of this world’s hatred.

Sylvia stood before it a long moment, breathless, motionless, awed, and then, still profoundly self-forgetful and absorbed, began to study it in its effect and details, bending forward and then moving back, stepping to this side and then to that. For the time that her entire attention was focussed upon the picture she was the old Sylvia again, Sylvia of the tranquil eyes and the gentle, deliberate movements.

She recognized at once that this was the highest expression of Arnold’s career; that it represented an almost incredible growth in his art. Not in any previous work had he shown such concentrated power, such exaltation and high nobility of feeling, and such mastery and such subordination of treatment; and Sylvia’s appreciation, for she had ever been an enthusiastic lover of the best that man has wrought, rose like a lark from the depths of her imprisoned spirit and lifted its wings and sang an answer to this clarion-call of genius.

In an intense but still tranquil absorption she moved from one canvas to another, inspecting each minutely, comparing one with another, then studying them as a whole.

The great golden letters set forth plainly Arnold’s theme: “Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free,” and on each panel was portrayed the supreme moment in the life of the world’s greatest dreamers – discerners and proclaimers of the Truth, that Truth which makes all things new and sends out unsuspected, undivined thought-worlds like golden balls spinning through the ether from the dim looms of Chaos.

Arnold had chosen that hour in the life of each of his conquerors when Man – the fearer and hater of dreams – rises in all the might of temporal power to crush Man the reflector of the Idea, and he had invested the bleak hill of Calvary, the gaunt and ghastly scaffold, the foul and narrow dungeon, with a splendor of light which made them antechambers to the Kingdom of God; while the purple and scarlet and gold of pomp and power, the machinery of repression, appeared as pitiful deceptions; and the ermined kings and prelates, the armored soldiery gathered to set the machinery in motion, as mad maskers and mummers cowering purblind before the light.

From each dreamer, manacled, crowned with thorns, twisted with torture, or hung with chains, there emanated the majesty and might of the soul’s eternal freedom, the white, ineffable irradiation of light, so that they, dying, seemed the manifestation of life at its fullest, most rapturous, and immortal moment; and the mob, which shrieked triumphant, the spawn of death spewed from some bitter maelstrom of ignorance and horror.

And Sylvia, trembling, admiring, adoring, still passed from one to the other, still leaned and looked, and looked again, until at last she drew a chair to her where her eyes might cling to the canvases and leaning her chin upon her hand, gradually sank into reverie.

So this was what the veiled, mysterious, beckoning figure had given to Arnold! No visions of sensuous beauty; but austere and lofty images of the soul’s struggled and triumphs. Ah well, what matter? She sighed heavily; what matter whether it were the flower-crowned, dancing daughters of the Venusberg, or some wan and tortured victor over illusion, with eyes unsealed and lips touched with the flame of his message? What mattered the character of the visions? Had they not taken him from her?

For a long time she sat thus, her head averted from the pictures, her eyes cast on the floor, her depression deepening, until at last her tranquillity fell from her, and she rose and began again her hurried, uneven pacing of the floor. Some dreadful tide with a sinister, hissing lap seemed creeping nearer and nearer her, until at last the black waters of hate rushed and roared and seethed about her, and she felt the awful inexorable drag of the undertow. She was lost in whirlpools of tortured thought, and then the undertow dragged her down.

On one of the tables near her she saw the sharp, thin, gleaming edge of steel, and she caught it up and made a rush, straight as an arrow from the bow, toward the central panel.

“Sylvia!” Hartzfield standing in the doorway had almost whispered the words, and yet she heard him, although the roar of many waters was in her ears. “Sylvia, what are you doing here?”

Instinctively she folded the knife in her cloak. “I-I came to see them.” She fought for controlled utterance. Her lips were dry. She could barely form the words. “I had to come.” The anguished heart of her burst through her lips. “I would not have chosen to come, but I had to. I could bear no more. I had to see what it was that had pushed me out of my place in your life, what it was that had changed your whole nature. I had to see in tangible form the work to which I had been sacrificed. Oh, Arnold, have I not a right to some of you, to some of your thought and consideration? Has love no rights?”

He did not answer her. He could not, but leaned the more heavily against the door, as though chained in some horrible nightmare, unable to move. His breath came in audible, painful gasps.

“You have thrust me out into some cold isolation as desolate and ice-bound as this awful winter – she made no effort to wipe away the tears rolling down her emotion-tortured face- “and I am young and alive. I am a woman, and I want to be loved.”

His eyes never left hers, but, wide and staring, clung to her as if fascinated by some image of unbelievable horror.

“And I am your wife,” her voice growing higher and shriller, “and yet I am completely shut out from all your interests. Do you call that being one? Do you call that union? And look!” her wild, gasping laughter rose and fell and echoed through the room. From the folds of her heavy cloak she drew the knife. “If you had not come just when you did, just when you did, I should have slashed the canvases to bits, slashed them to bits and trampled on them.”

He was across the room in a bound, his hand like a steel vise on her wrist.

“Adele!” the name seemed forced from him, his white lips twisted over it.

“Adele!” she repeated, and grew suddenly calm, not even striving to free herself from the grip of his tense fingers pressing cruelly into her flesh. “Why do you say her name? Twice this evening you have called me Adele.”

His face was more ghastly than ever.

“It was so she looked; so she spoke the night she stole here.”

“The night she stole here?” Sylvia repeated, still calmly. “What night?” The knife fell from her fingers and clattered on the floor; he thrust it far with his foot.

“The night she cut my pictures to ribbons; my just finished picture of Love; and then drove the knife into her own heart, here, where you stand. And you, Sylvia, have spoken her very words, duplicated her very actions. Oh, in what horrible dreams are we groping?” His voice broke poignantly. He looked wildly about him as if to assure himself of some fantastic dream-surroundings from which they would presently emerge; and then upon his face dawned a great light of horror and awakening commingled. “I see it. I see it now.” He cast his arms about her, clasping her close as if to shield her from some dreaded menace. “Oh, my God, is it possible? May a passionate and powerful consciousness so stamp its personality upon the environment in which it lived that it persists and continues to exert its subtle and poisonous influence upon sensitive natures?”

“An influence?” she repeated, dazedly, winding her arms more tightly about his neck, and shrinking, shuddering against him – “an influence- Oh, you do not know-!”

“Ah, Sylvia, poor Sylvia, do I not know? Have I not struggled in those coils? But during her life. I have never felt it since.”

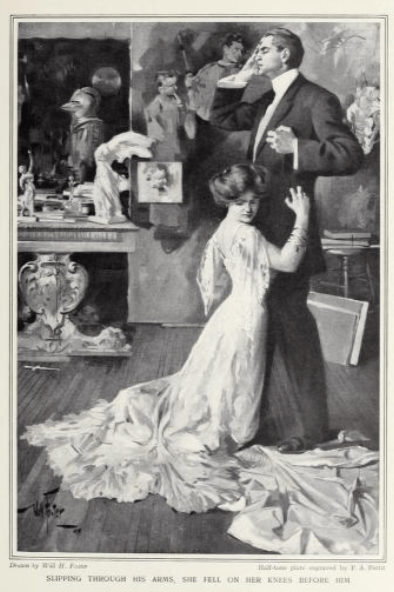

“But how did you save yourself? How did you save yourself?” She slipped through his arms and fell on her knees before him, clutching him with gripping fingers.

“My work saved me.” He drew his hand across his brow. “Yes, my work saved me. Living or dead, she could not touch the best in me, the longing to create images of truth and beauty.”

“But I have no art to save me, no highest in me.” She swayed brokenly from her knees to the floor and lay there, her proud and delicate head on her out-thrown arms.

“Oh, Sylvia!” he knelt beside her, covering her cloudy hair with kisses, “the highest in you is so high that I have never dreamed of reaching it; but it has lifted me; oh, it has. This work, the best of my life, would have been an impossibility without you. Idea after idea, conception after conception, has been rejected, because I saw you always, your head uplifted in a purer ether, the stars a scarf about your shoulders, beckoning me higher. The crystal stream of your affection has soothed and restored my fevered spirit. It is in your love, Sylvia, your understanding and sympathy, which never bound nor fettered me, that I have found the freedom of the spirit which has enabled me to work out my dreams.”

“Ah, tell me again! Make me believe it!” Her voice was as the voice of a sobbing child.

Again and again he told her with words and caresses, and Sylvia, listening, lifted her fallen head, rose to her knees and then to her feet. She breathed a rarer ether again; the light of the morning was in her eyes. “Then I, too, am free,” she cried. “If the best of me has helped you to create these pictures, then the best of me is too high to be reached by any lower influences. “Look, Arnold, look! It is dawn. Come, we must go home.”

He shrank, his face darkening. “Not there. You cannot go back there. Not into that rose-colored hell.”

She raised her eyes to his, clear and tranquil to their depths. “There is nothing there than can touch me now. To-day I shall begin to change everything. Come.”

They left the studio; the glory of another day was flashing across the sky and over the hilltops, and in one brief moment of clear vision Arnold and Sylvia saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the former things were passes away. Then, hand in hand, through the black, sentinel trees stretching away to the sunrise and across the dawn-flushed snow, they walked together in love’s great and happy silence.

Good one! The images are extraordinary.

LikeLike